I am often asked whether the Germans had any idea that the British were successfully breaking Enigma during the war.

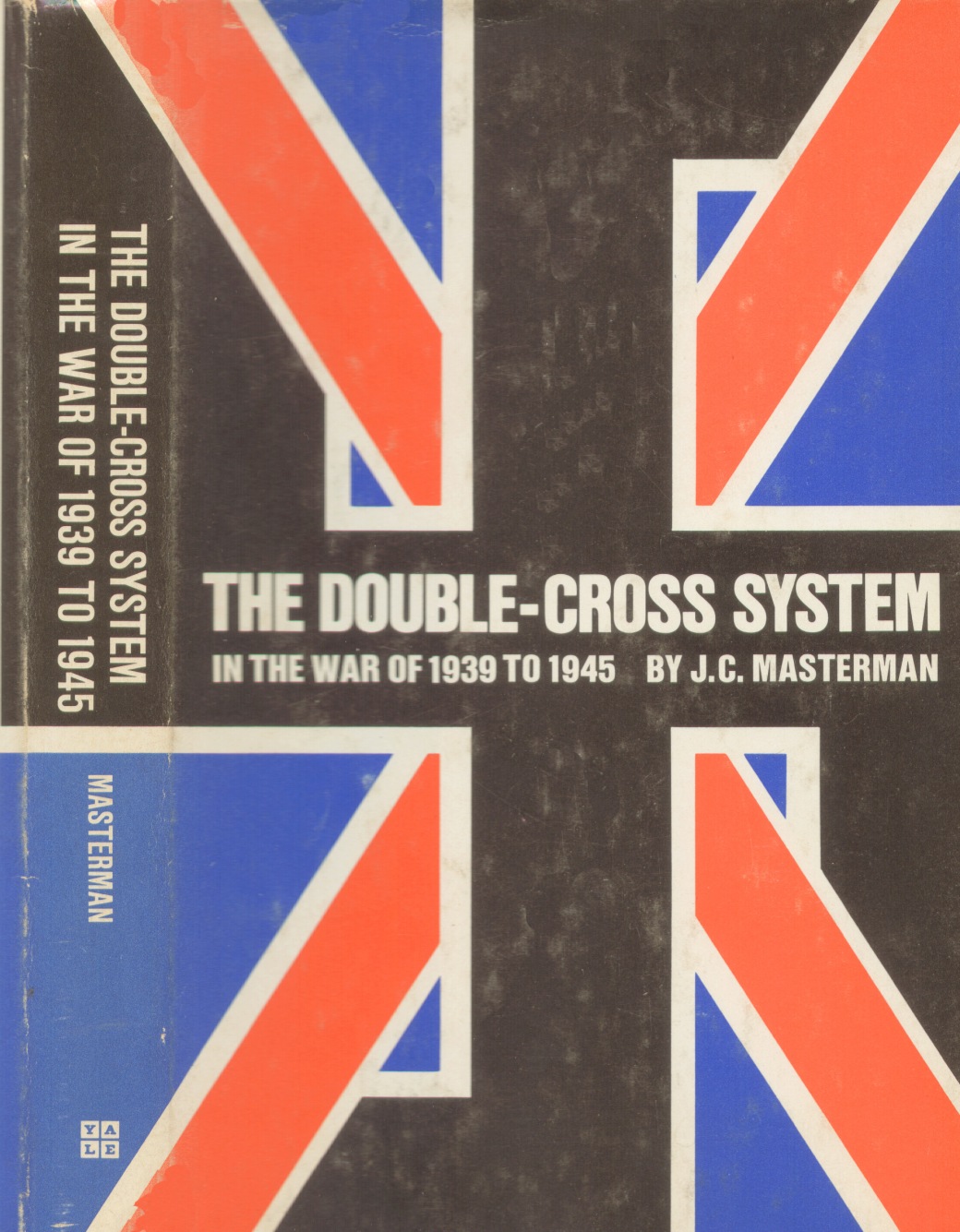

Surely, they say, there were German spies in Britain who would have been able to pick up some clues, and to report their findings back to Germany? It often comes as a surprise to them when I tell them that, firstly, all the German spies in Britain were directly controlled by the British, and that, secondly, British achievements were not known of in Germany until the 1970s.

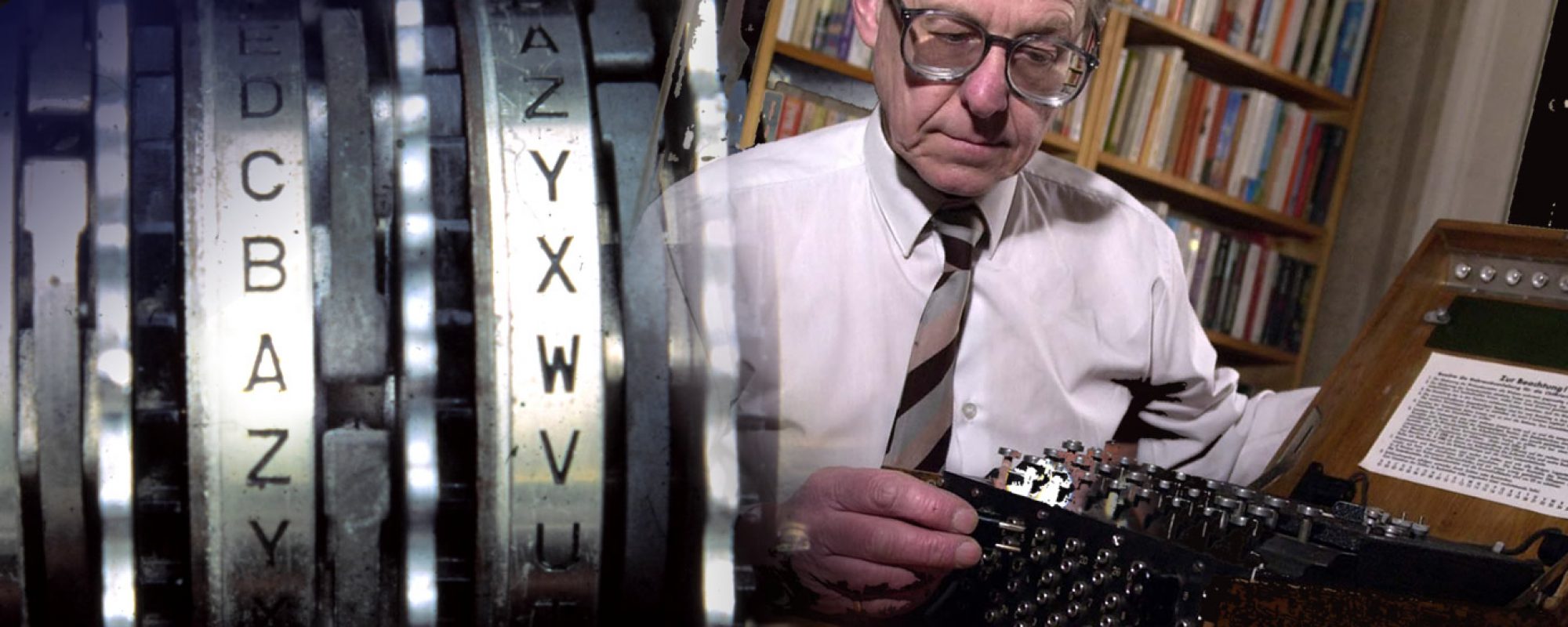

It seems that the Enigma machine – or, rather, its ciphers – were seen in Germany as unbreakable. After all, there were theoretically 3 x 10114 possible cipher patterns which the basic three-rotor machine could create, and testing all these possibilities one after the other is beyond modern computing power even now, and so was well beyond anyone’s wildest dreams during WW2.

With this exaggerated belief in the inviolability of the Enigma system, its users never stopped to think – or even to test – whether it could really withstand an organised attack using mathematics rather than the ‘brute force’ approach of attempting to test all those possibilities in succession. (See: War Hackers: Why Breaking Enigma is Still Relevant to Cybersecurity Today).

There were occasions when Allied successes in combat were such that questions were raised on the German side – investigations were set up to identify what had gone wrong, had valuable information been leaked?

Inevitably, when all the possible explanations were examined, unfounded faith in Enigma steered the investigators away from realising that Enigma might actually have succumbed to a sustained mathematical attack.

With hindsight, we can now identify occasions when more rigorous analysis might have revealed to the Germans that Enigma was, at least, breakable, even if not broken. Such a conclusion might have prompted tightening up or changing the way in which Enigma was used, or perhaps changing the wiring patterns of the rotors. The latter never happened, and such changes as were made to the operating procedures were never sweeping enough to shut out Bletchley for long.

Of course, great care had to be taken over Allied use of Intelligence derived from breaking Enigma. Over-hasty or injudicious use of such Intelligence could well have suggested to the Germans that Enigma-encrypted messages were being read. No-one on the Allied side, therefore, was permitted to base any action on a decrypt, unless there was also another way in which the relevant Intelligence might have been acquired.

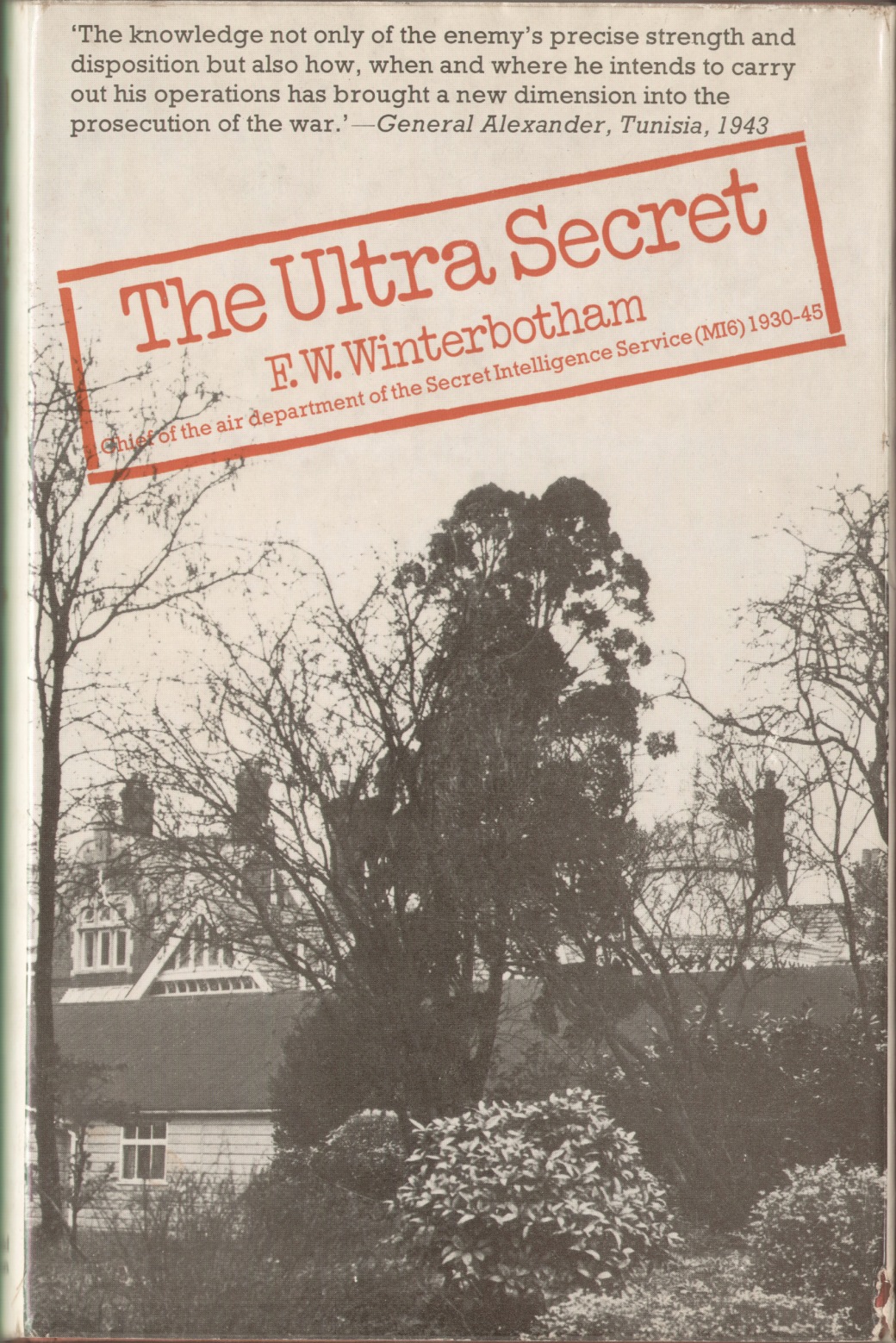

The care with which Enigma-derived Intelligence was handled prevented its source from being discovered, and this, together with Germany’s unjustified faith in the machine’s power, meant that knowledge of Allied breaking of Enigma remained a secret not just throughout the war, but until 1974, when The Ultra Secret, a book written by RAF Intelligence officer Frederick Winterbotham, revealed the truth.

Even so, there was a perilous moment when Schellenberg’s handbook for the planned invasion of Britain (produced in 1940) reported that MI6 had moved its Communication Section from Broadway to Bletchley Park, and that its duties included Wireless/Radio communications.

The implications of this accurate observation, correctly linking MI6, Bletchley, and wireless communications, were never followed up. The evidence lay upon the printed page – but was never spotted.