There is a seductive story that after the Second World War Britain sold off captured Enigma machines to other countries claiming, no doubt, that these machines were the best crypto devices available, and that the ciphers they created were completely unbreakable. Perfidious Albion, the story goes, then used the wartime techniques developed at Bletchley Park to read any Enigma-encrypted wireless traffic generated by these benighted customer countries. Is there any truth in such stories? They have been much repeated, by many authors. The earliest mention of this ruse that I have yet found was made by David Kahn, no less, when he reviewed Winterbotham’s The Ultra Secret for The New York Times in 1974. Kahn says

It seems that after World War II, Britain gathered up as many of the tens of thousands of Enigmas as she could find and later sold them to some of the emerging nations. (This is a quotation given in Enigma by Wladyslaw Kozaczuk.)

Ten years later, Gordon Welchman’s book The Hut Six Story quotes a paper by Professor Jean Stengers of the University of Brussels as revealing not only that ‘after the war, England sold a considerable number of Enigma machines to certain less developed countries’ but also perceptively suggests that this could explain Britain’s determination to keep secret the fact that Enigma ciphers had been already been extensively broken at Bletchley Park. A couple of years later, Nigel West claimed in his 1986 book GCHQ that ‘many thousands of Enigma machines’ were recovered from Germany in 1945. He does not say that all, or indeed any, were recovered by Britain, but he does say that Britain distributed reconditioned Enigmas to friendly governments, and that even in the late 1970s there were many hundreds of Enigmas in operation all over the world.

In 1987, David Hooper, a careful and considered writer, wrote in Official Secrets that

. . . the British government had after the war sold a number of these Enigma machines to unsuspecting developing countries, including Indonesia, without informing their governments that the British could now read their coded messages.

James Rusbridger’s The Intelligence Game was published in 1989, and contains the statement that Britain and America ‘sold off to many smaller countries reconditioned Enigmas at extremely cheap prices’. In 1991, Chapman Pincher wrote, in The Truth about Dirty Tricks, that MI6 and GCHQ jointly organised a scheme by which

hundreds of Enigmas recovered in Germany were reconditioned and sold to other Governments, mainly in the Third World, as a completely safe way of communicating.

Kahn himself had made no mention of such sales in the first edition of his monumental The Codebreakers (1967), but in 1996, in the second edition, he says

The British government . . . had given the thousands of Enigma machines that it had gathered up after the end of the war to its former colonies as they gained independence . . .

Richard Aldrich, in a contribution to Action This Day (edited by Michael Smith and Ralph Erskine) says that in the late 1940s

Some neutral states were persuaded to adopt Enigma or Enigma-type machines . . . in the belief that these machines provided a secure means of communication . . . a belief that GCHQ did nothing to undermine.

This was published in 2001, and the statement was retained in The Bletchley Park Codebreakers (Erskine & Smith), which was a revised version of Action This Day, but Aldrich makes no such mention in his GCHQ: the uncensored story (2010).

* * * * * * * * * *

Thus we have a number of authors, some of whom are solid reliable historians, putting forward the same basic story, albeit with variations. The story is that Britain sold or gave WW2 Enigma machines to unsuspecting countries after the war, without revealing that Britain would then be able to read any Enigma-encrypted traffic they might send, and this provided one reason (perhaps not the only one) for keeping Bletchley Park’s wartime successes a secret. Frustratingly, not one of these writers gives any source for the interesting information that they put forward. The mere fact that eight leading writers all tell the same basic story does not, of course, prove that it’s true (we can’t ignore Tom Lehrer’s advice that if you plagiarise, you must remember, always, to call it ‘research’), and I have not yet come across any official admission that these sales actually occurred. On the contrary, official historians deny that there were any such sales.

On 6 January 2018, Tony Comer, departmental historian at GCHQ, was quoted in The Daily Telegraph as saying ‘With the defeat of the Germans . . . . there was nobody left using Enigma’, but conversely admits that ‘50 bombes and 20 Enigma machines were kept in deep storage’. He dismisses the idea that Britain sold Enigma machines to neutral countries as ‘a complete myth . . . we now know there was no target’. However, as the Russians knew about Enigma, their client states would very obviously have been targets, and I was approached in 2001 by a man who told me that he’d been operating bombes at Eastcote in 1948, where 16 were still operational after the end of the war.

John Ferris, in his long-awaited history of GCHQ, Behind the Enigma (2020), tackled the subject head-on: ‘The story that Britain deliberately flogged copies of the Enigma to foreign countries is false.’

* * * * * * * * * *

So, two historians, with access to extensive archives, dismiss the story completely. Mind you, Ferris has not chosen his words well. What does the word ‘deliberately’ add to that sentence? Why use a word like ‘flogged’ in what is supposed to be an academically respectable work? What does ‘copies’ mean here? – the basic story is that what were being sold were original Enigmas. Before accepting what these two historians assert, we must remember that they are basing their assertions on a negative. They provide no sources, so presumably they have not found any documentary evidence that the story is false. That is not, by itself, proof; Ferris and Comer give no more evidence for their statements than do Kahn and Welchman, maybe even less.

If, say, Kahn’s original statement had been published in 2020 rather than 1974, and Ferris’s in 1974 rather than 2020, we would simply conclude that Kahn had found a source or sources not available to, or not found by, Ferris. We expect later writers to have wider and deeper access than earlier writers. But perhaps Kahn, nearly 50 years before Ferris, did have access to records which have since been destroyed, or to people who have since died. Selective destruction of records does occur, and most of the makers and implementers of policy made in the 1940s and 1950s are long since dead.

* * * * * * * * * *

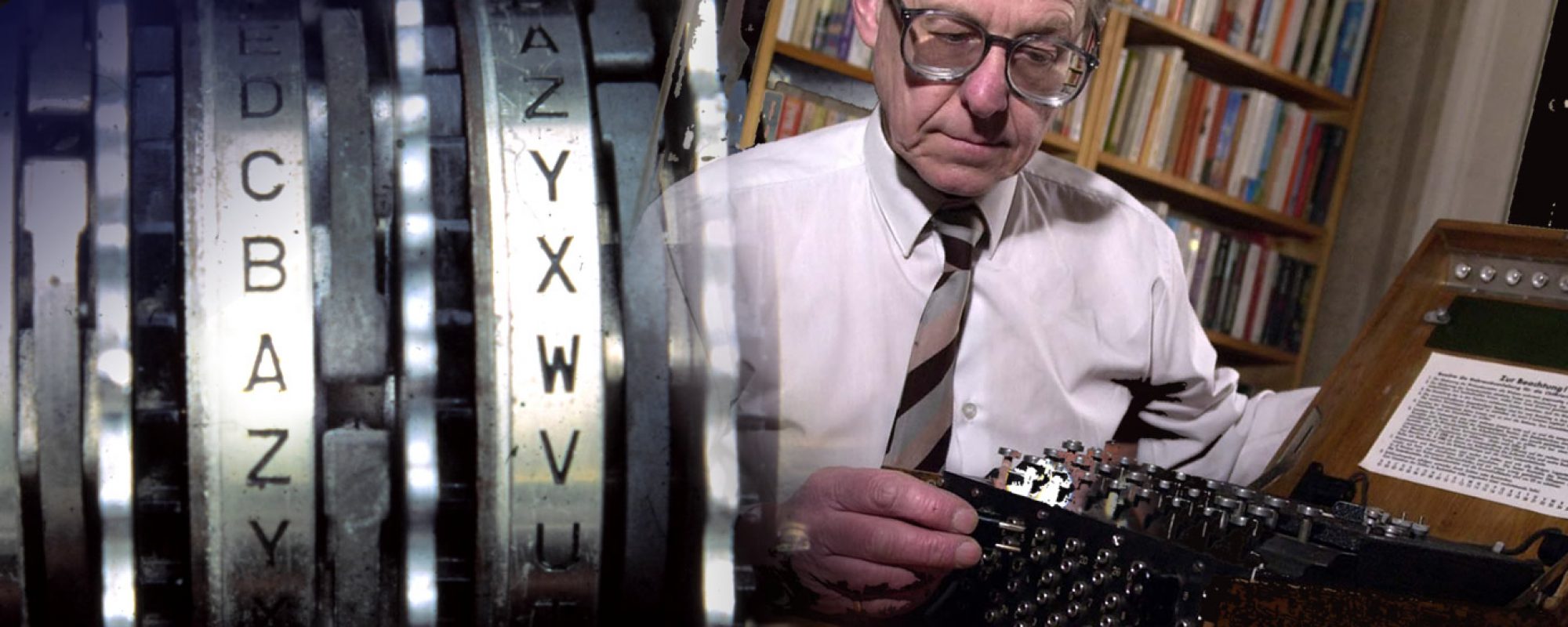

There is one further factor we must consider – the machines themselves. Is there any evidence for hundreds of machines being used postwar? There is no known record of how many Enigma machines were held by Britain, although a memo in 1953 referred to ‘a large number of E machines carelessly stacked, out of their cases . . .’ in a Royal Naval Depot. These were not destroyed until 1959. We do know that Norway used Enigma machines (with rewired rotors) for some time after the war. We know that Israel obtained perhaps 30 Enigma machines from somewhere a few years after the war. At least two of these survive, with keys re-labelled with Hebrew characters (although Comer says that UK had no knowledge of any machines being given to Israel). We also know that Italy’s Guardia di Finanzia used Enigma machines as late as 1985.

In addition, Enigma machines were available, presumably as ‘Government Surplus’ both in USA and in Germany. In USA, commercial brochures advertising the Enigma machine were being printed well after the war, possibly as late as 1958. In Germany, Steeg’s 1968 catalogue showed photos of a 3-rotor machine, and stated that they had 135 in stock.

There is, therefore, plenty of evidence for Enigma machines being available and being used for decades after the war. West may even have been right to say that there were hundreds in use in the late 1970s. There is also good evidence that some East German Departments were using Enigma machines at least as late as 1956, and that the Americans were using a Bombe to attack these (see KVETKAS).

So Enigmas were still being used by friendly countries, neutral countries and enemy countries, for years after the war. It seems that both the USSR and Britain could have had both motive and ability to distribute Enigmas to client countries. If Comer did say ‘With the defeat of the Germans . . . there was nobody left using Enigma’ and ‘we now know there was no target’, this does not seem to be the whole story.

On balance, the evidence that Britain gave or sold Enigmas postwar, and retained and used Bombes in the postwar period, is very slender, and the basic story may rest on a misunderstanding about Israel, and the fact the Enigmas were being actively traded for years after the war. However, unless a register of Enigmas held by, and disposed of by, Britain comes to light, statements to the contrary must remain unsubstantiated, even if strongly phrased.

For their advice and assistance, my thanks go to Mike Barbakoff, Howard Craston, John Jackson, and Tom Perera.

Sources:

ERSKINE, R & SMITH, M. The Bletchley Park Codebreakers. Biteback, 2011. p359.

FERRIS, J. Behind the Enigma. Bloomsbury, 2020. p271.

HOOPER, D. Official Secrets. Secker & Warburg, 1987. p197.

KAHN, D. Codebreakers. 2nd edn, Scribner, 1996. p979.

KOZACZUK, W. Enigma. Arms & Armour, 1984. p219.

KVETKAS, W. The Last Days of Enigma. US NSA Doc 310787, 1998.

States Enigma used by East Germany until 1956; messages broken by Bombe in USA.

PINCHER, C. The Truth about Dirty Tricks. Sidgwick & Jackson, p252.

RUSBRIDGER, J. The Intelligence Game. Bodley Head, 1989. p21.

SMITH, M & ERSKINE, R. (eds). Action This Day. Bantam, 2001. p408.

STENGERS, J. ‘La Guerre de messages codés’ in L’Histoire No 31, Feb 1981.

WELCHMAN, G. The Hut Six Story. McGraw-Hill, 1982. p17.

WEST, N. GCHQ. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1986. p3.